She sits in London, in Room 19 of the British Museum (open only 11-3, but often not even that). A solitary caryatid, one of six that graced the Erechtheion, a temple to the north of the Parthenon on the Athens Acropolis. The other five live in Athens, at the Acropolis Museum. Greeks often call her “the Lost Sister.”

New Theme (Series)

Welcome to Tales of Separation, a series within the Images of Antiquity newsletter about significant pieces of ancient art that are separated from their places of origin, typically located now in major museums in Western Europe or North America. But that could be almost everything in the ancient galleries of those museums, you say?!! Well, yes, but as it’s my newsletter, I get to choose!

To be clear, I’m not necessarily anti-museum - in fact, I love museums and spend a huge amount of time in them. I’ll even grant the argument that sometimes removing these pieces from their original locations meant saving them from almost certain destruction. But looking from today's perspective, you will likely detect a bit of a “repatriation bias” from me, particularly when it comes to major pieces with really significant cultural importance and when “reunification” would allow a better understanding of a site as a whole.

OK, back to the Lost Sister…

The Erechtheion

The Erechtheion was the most important religious building on the Athenian Acropolis. It was built during pauses in the Peloponnesian War (421-415 and 410-406 BCE) and was the last of the great works envisioned by Pericles, replacing the Old Temple of Athena Polias, part of which was destroyed by the Persians in 480 BCE. This was the destination of the Panathenaic procession, and the altar in front of the temple is where the great sacrifice at the conclusion of the procession took place. The name "Erechtheion" was given to the building later and connects it to the mythical King Erechtheus, who was worshipped in the same location.

The temple has an unusual design, due in part to the uneven surface on that part of the Acropolis. It also reflects the fact that the temple needed to accommodate various ancient religious cults and incorporate a number of sacred elements, including the graves of the mythical kings of Athens, Kekrops and Erechtheus, and the three signs Athenian tradition claimed were physical evidence of the contest between Athena and Poseidon to become the patron saint of Athens: the olive tree Athena offered to the city, the mark of Poseidon's trident where he struck the rock and the spring of salty water that then gushed forth.

The Caryatids

The Erechtheion has two porches or porticos, on its north and south sides. The porch on the south side has a roof supported by six female figures, known today as Caryatids, taking the place of the columns. It is thought that they were carved by a sculptor in the workshop of Alkamenes, a pupil of Pheidias.

One interpretation of the Erechtheion Caryatids is that they are an above-ground monument for the tomb of Kekrops, located directly underneath - the choephoroi (libation bearers), rendering tribute to the dead king, with phialai (shallow libation bowls) held in their hands. An inscription on the temple labels them simply Korai (maidens); the name "Caryatids" was given later. Pausanias, for example, says the Caryatid statues represent dancers from Karyes, a town in Laconia, on the Peloponnese - every year, female dancers (originally just from Karyes; later, from elsewhere in Laconia as well) would perform the dance of “caryatis” around a statue of the goddess Artemis Karyatis (of the walnut trees) at a summer festival called Karyateia.

The Lost Sister

The Caryatid in the British Museum arrived in 1816 with Lord Elgin's other marbles. In November 1798, Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, was appointed as "Ambassador Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of His Britannic Majesty to the Sublime Porte of Selim III, Sultan of Turkey" (at that time, Greece was part of the Ottoman Empire). While in Greece, Lord Elgin had intended to document the sculptured portions of the Parthenon, using artists to take casts and drawings. But in 1801, he also began to remove material from the Parthenon and its surrounding structures. From 1801-12, his agents removed about half the surviving Parthenon sculptures, as well as sculptures from the Erechtheion - including one of the Caryatids, the Temple of Athena Nike and the Propylaia, sending them back to Britain.

Elgin then sold the sculptures to the British government in 1816, and by an act of parliament, the British Museum Act 1816, the collection was transferred to the British Museum on the condition that it be kept together. Later, another act of parliament, the British Museum Act 1963, was passed, forbidding the British Museum from disposing of its holdings (with a few small exceptions).

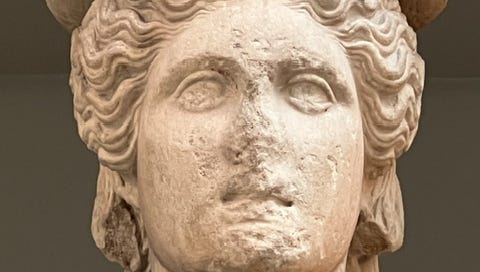

So the Caryatid arrived at the British Museum. Originally, she was second from the left in the row of four at the front of the south porch of the Erechtheion. She wears a peplos (tunic), with a short cloak hanging from the shoulders. Her long, thick hair is braided around her head, and falls on each shoulder and down her back. In other Greek architecture, many caryatids carry a cist, or ceremonial basket, on the head to connect with the architecture they support. Here instead a cushion supports an unusual column capital.

The Other Sisters

The other five Caryatids live today in the Acropolis Museum in Athens (although one is only fragments as it was smashed by a Turkish cannonball). They were removed from the Erechtheion in 1978, much corroded after nearly two more centuries of weathering, and replaced by cast reproductions.

In December 2010, the Acropolis Museum commenced a program of conservation and restoration of the Caryatids, which was completed in June 2014. This work was conducted in the museum gallery itself - the Museum decided not to risk the fragile sculptures by moving them out of the gallery, but also wanted to give visitors an opportunity to observe the conservation procedures, which normally happen out of view in conservation laboratories. I can confirm this was fascinating - I couldn’t find any of my photos of the conservation work to share here, but I remember seeing the work in progress! The surfaces of the sculptures revealed after the conservation work were preserved in excellent condition, with visible traces of the tool marks of the ancient marble workers. Traces of previous conservation work dated from the Roman period to 1971 were also preserved.

Politics of Repatriation

For decades, Greece has actively campaigned for the Lost Sister's return, as part of a broader initiative to repatriate the Parthenon Marbles. In 1983, the Greek government formally asked the UK government to return "all the sculptures which were removed from the Acropolis of Athens and are at present in the British Museum," and in 1984, it listed the dispute with UNESCO. In 2013, the Greek government asked UNESCO to mediate between the Greek and UK authorities on the return of the marbles, but the UK government and the British Museum declined UNESCO's offer to mediate. In 2021, UNESCO concluded that the UK government had an obligation to return the marbles and called upon the UK government to open negotiations with Greece.

Even at the time, Lord Elgin's actions were controversial: some in Britain (like Lord Byron) characterized them as vandalism or looting, and in February 1816, before Elgin sold them to the UK government, a UK parliamentary inquiry held public hearings on whether Elgin had acquired the marbles legally. Exactly this question has been the subject of considerable international dispute ever since, but British inquiry at that time concluded it was legal: Elgin had argued that the work of his agents at the Acropolis, and the removal of the marbles to Britain, were authorized by a firman from the Ottoman government obtained in July 1801, and a second one in March 1810.

Current scholars are divided on the legality of Elgin's authority to acquire the marbles - with debates around the records of the firman (and whether it really was an official firman at all) and the wording (permission to actually remove sculptures from buildings or only to remove rubble on the ground), among other things. Plus there’s the question of whether permission from an occupying power (the Ottoman Empire) should be considered binding. (It is also interesting that in May 2024, a spokesperson for Turkey, a successor or the continuing state of the Ottoman Empire, denied knowledge of the firman and stated that Turkey supported the return of the marbles. But they too have their own lost antiquities to reclaim…) Of course, even if one concludes the removal was legal, there’s a moral argument of whether antiquities so central to the Greek identity should be returned in any event.

On the other side, there are a variety of arguments: Elgin's authority was legal; removing the marbles protected them from further damage (no longer persuasive following the construction of the Acropolis Museum in Athens and revelations about questionable conservation practices at the British Museum); more people can see the marbles at a “universal museum” like the British Museum; repatriation would take an act of the UK parliament. Perhaps most challenging is the “slippery slope” argument: as I acknowledged at the beginning of this post, there are so many pieces in museums worldwide that were likely stolen from the original location and indeed, many of them have national significance - how do you draw a line? Should we really empty out museums?

There was hope briefly in late 2022, when British and Greek authorities resumed negotiations on the future of the marbles, but this process seemed to completely break down in November 2023. Now again, however, talks are underway, as reported publicly in January 2025. Supposedly, significant progress has been made, with potential final resolution in 2025. But… not all the sculptures are expected to return to Greece. Reportedly, the Parthenon marbles - the reliefs and other sculptures removed from the Parthenon itself - are the subject of the deal; they may be permanently housed in the Acropolis Museum while major Greek artifacts would be offered for extended exhibitions in London, a model that has been followed in other repatriation agreements. But the pieces not considered essential for reuniting the Parthenon’s artistic and historical narrative may not be part of the deal - notably, the Erechtheion Caryatid.

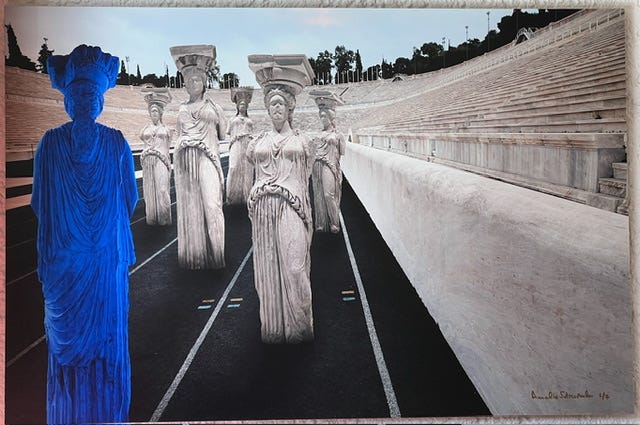

So it sounds like the Lost Sister may continue to sit in solitude in her London home for a while yet (maybe she will be easier to see if the Parthenon marbles are gone?). For now at least, she may only be able to visit her home and sisters in our imaginations.

Sources: Materials from Acropolis Museum, Athens, & British Museum, London; Wikipedia; Costis P. Papadiochos, Greece and UK Close to Marbles Deal, Jan. 13, 2025, ekathimerini.com.

Over the next few days, there will also be several related posts on Instagram, which you can check out here: Instagram. And if you liked this post, I’d be grateful if you would share it with others.